Mary, who is 24 but looks barely 18, has already experienced more than enough betrayal for any lifetime. Shyly but deliberately, she told of feeling sick at 16 and being diagnosed with HIV. After her mother — her only provider — was sent to prison, an aunt took Mary in, but forced her to sleep in an open-walled shed behind the house. Then she was raped by a boyfriend. “I went home crying and bleeding,” she recalled. Mary told no one, fearing she would be turned out on the street. “I kept quiet, by myself.” Four months later, she learned she was pregnant.

For the sake of the child — a girl born HIV-free — she took antiretroviral drugs. But then a friend introduced her to a Christian pastor. “He lays his hands on you and says the sickness will go,” Mary remembered. “I believed him.” She put her medicines down the toilet and stopped treatment for two years.

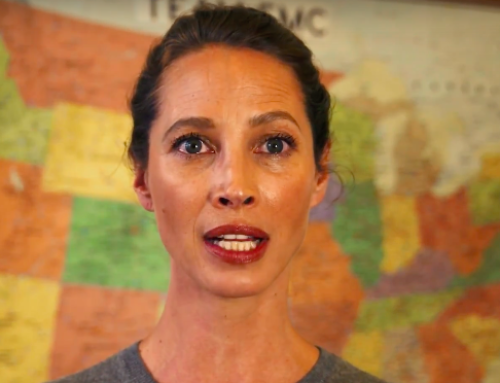

The Ng’ombe Community Health Centre’s “Youth Friendly Corner,” Lusaka, Zambia.

Photo credit: Anne Jennings

Last year, Mary got married and initially did not reveal her medical history to her spouse, fearing another rejection. “It is difficult to stand up and say you are positive,” Mary explained. “It was my secret.” But a counselor persuaded her to be tested again along with her husband. When her test came back positive and his negative, she ran crying from the clinic, convinced she would be abandoned. But her husband followed after her. “He said to me, ‘This is not the end of the world.’ ”

True enough. Yet it is hard to imagine why the world — family, pastor, rapist — should be so relentlessly cruel to such a sweet and gentle young woman. Gentle, but not fragile. Just revealing her status and story to strangers, in a place where stigma is strong, took some of the greatest personal courage I’ve witnessed. (I traveled to Zambia as part of a task force convened by the Center for Strategic and International Studies to examine issues related to women’s and family health.)

Stories like Mary’s — in the millions — add up to one of the most urgent health crises of our time. While vast progress has been made in AIDS treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, barely a dent has been made in HIV infection rates among young women (which are significantly higher than among young men). With the youth population of Africa booming (40 percent of Zambians are under 16), a realization is dawning: The AIDS epidemic will be uncontrollable unless the number of infections among young women is rapidly and dramatically reduced.

In Zambia, about 11 percent of women become HIV-positive by age 24. A sad variety of cultural factors are implicated. Gender-based violence. Child marriage (in spite of national laws against it). A male-dominated society means that young women often lack the power to negotiate safer sex or to access health services without the permission of male partners. Extreme poverty can lead young women to engage in transactional sex, but so can the desire for consumer goods that demonstrate status among girls from wealthier backgrounds.

High rates of HIV infection among young women are a medical crisis for which there is no purely medical answer. Norms need to be changed. The empowerment of young women has become an essential health priority. Data from Botswana show that just keeping girls in school decreases the rate of HIV infection by 12 percent each year.

There is now significant focus and funding dedicated to this issue from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The U.S. global AIDS coordinator, Dr. Deborah Birx, has announced an initiative called DREAMS, designed to dramatically reduce new HIV infections in adolescent girls and young women in high-burden “hot spots” in 10 African countries.

Here in Zambia, the target population is 63,000 vulnerable young women in three areas. The theory: Surround them with support and services in every part of their lives. HIV testing and counseling. Contraceptive information and access. One-stop facilities to report gender-based violence and receive care. Financial literacy programs. Educational subsidies. Outreach to religious and traditional leaders. Outreach to young men to challenge destructive gender norms and attitudes (like how someone, at some point, reached Mary’s husband).

If this model proves effective, it will need to be quickly brought to scale. Sexism, it turns out, is not only unfair but also unhealthy. To stop an epidemic, young women such as Mary, no longer quiet, must no longer feel alone.

This op-ed was originally published in the Washington Post on April 21, 2016