Since the 1980s, adolescent girls and young women have migrated from Ghana’s three northern regions to Accra and other large cities to search for better economic opportunities and escape interethnic conflict, early marriage, and rural poverty. These women, who predominantly have no formal education, often end up living in urban informal settlements and working as kayayei (female head porters). For eleven or so hours per day, in the sweltering heat, the kayayei move goods throughout Accra’s bustling markets for wholesalers, traders, and shoppers in exchange for a few cedis (Ghana’s local currency). The kayayei can be seen, from morning until dusk, making their way up and down the maze of alleys that constitute the market areas, weaving in and out of the thick flow of city traffic, carrying sometimes more than their own weight on their heads. While there is little data on the kayayei, there are an estimated 160,000 in Accra.

In June 2016, I traveled to Ghana as part of a delegation from the CSIS Task Force on Women’s and Family Health to examine U.S.-Ghana bilateral cooperation on reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) issues in a context of ongoing, rapid economic growth. Ghana reached lower-middle income country status in 2011.

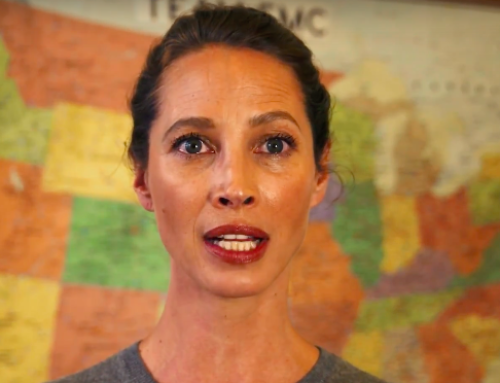

In Accra, we visited the Agbogbloshie informal settlement and had the opportunity to meet with a group of kayayei to learn about their experiences and challenges. Formerly a lush mangrove swamp, the Agbogbloshie settlement was established roughly two decades ago to temporarily house internally displaced people fleeing interethnic conflict over chieftaincy and land ownership in northern Ghana. With an estimated 40,000 residents, Agbogbloshie is today one of Accra’s largest slums. It is situated northwest of the Central Business District and etched into the Korle Lagoon, which flows into the Gulf of Guinea. An estimated one-quarter of residents make their living within the slum itself.

Agbogbloshie is characterized by its pollution, squalor, and residents’ lack of access to basic services. Locals sometimes refer to it as “Sodom and Gomorrah”. Agbogbloshie is one of the world’s largest electronic waste dumping sites. E-scrappers, some of whom are female, can be seen without any personal protective gear rummaging through and breaking apart discarded electronic appliances in search for useful marketable parts—copper, aluminum, and other materials—and burning the rest. The kayayei who live and work within the settlement face great risks to their health and safety, including diarrheal disease, upper respiratory infections, and gender-based violence.

During our visit, we learned that high-population density, poor waste management, lack of access to safe drinking water, and inadequate sanitation make Agbogbloshie a ready catchment area for gastro-intestinal and other infectious diseases, including cholera. When entering the settlement, one is immediately struck by the sight and smell of raw sewage running in open culverts at the edge of the road, the open defecation, and the dark, contaminated waterway connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. While there are public toilets and bathhouses in Agbogbloshie, residents are required to pay small fees for their use. In our conversation with the kayayei, many identified lack of access to free water and sanitation facilities as an important challenge. Slum Dwellers International, through its local affiliate, People’s Dialogue, is working to improve living conditions in the settlement.

The kayayei also face physical and sexual abuse; their young age upon arrival and lack of strong family ties or kinship networks within the slum make them highly vulnerable to gender-based violence, including rape and its potential consequences, such as unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion. We learned that as a safety measure the kayayei sleep in groups at night along the stalls in the market area.

In 2012, under the USAID-funded Support for International Family Planning Programs (SIFPO) project, Marie Stopes International Ghana (MSIG) provided the kayayei with access to family planning information and services, voluntary counseling and testing for HIV, and referrals to government health facilities. They also organized group discussions in the community with the Ghana Police Service’s Domestic Violence and Victim Support Unit. While MSIG no longer receives support from USAID and has had to scale back some of these activities, the original U.S. investment was used to leverage other donor funding to enable certain aspects of the outreach to continue.

In our discussion with the kayayei, we learned that while many migrate to Accra with the expectation of eventually returning to their communities in northern Ghana, their move often ends up being permanent. Some of the women begin families of their own in Agbogbloshie, with their daughters and grand-daughters tending to ultimately work as kayayei themselves. We met several young kayayei mothers who said they envisioned a different future for their daughters and one older kayayei, named Hawa, who continued to live and work in Agbogbloshie, taking care of her grandchildren, so that her children could pursue economic opportunities elsewhere. But with an estimated 15,000 young women continuing to arrive in Accra from the northern regions annually, the ranks of the kayayei continue to grow.

Ghana presents a success story in many ways and its recent economic development is widely touted. Accra’s poverty incidence fell by 20 percentage points between 1992 and 2012; however, the kayayei have been largely left out from this development. Despite the hard lives they lead, the kayayei seem to conclude that life in Accra is superior to the even harsher poverty and deprivation in northern areas. On the one hand, interventions should focus on expanding access to education for girls and addressing rural poverty in northern Ghana. At the same time, we heard that efforts to address gender-based violence; improve the water, sanitation, hygiene conditions of the settlement; and expand of targeted community outreach health services could help to address their needs.