“You can’t walk with one leg only,” said Dr. Awa Marie Coll-Seck, Minister of Health of Senegal, when referring to the private sector as an integral part of her country’s health system. She made the comment during a meeting with a delegation from the CSIS Task Force on Women’s and Family Health that included representatives from the U.S. Congress and the global health community. I was traveling with the delegation on behalf of Rabin Martin President and CEO, Dr. Jeffrey L. Sturchio, who is a member of the Task Force.

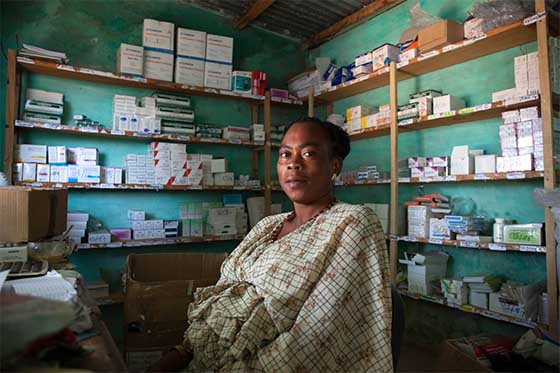

Oulimata Diop poses in front of the family planning section of the Centre de Santé de Birkelane pharmacy where she works filling prescriptions. The Center avoids contraceptive stock outs with IntraHealth’s Informed Push Model of distribution, which delivers supplies before they are needed so women can choose the best option for themselves –not simply what’s in stock.

Photo Credit: Caitlin Healy

Cooperation between government and the private sector has played a significant role in Senegal’s remarkable progress in increasing contraceptive prevalence, which jumped from 12% in 2012 to 20% in 2014 following years of stagnation. Key to this success was the fact that government had a clear and costed plan, along with the commitment and resources to reach its targets. Availability of supplies is also a critical component.

While many programs played a role in this success, one important contributor has been an innovative supply chain program called the Informed Push Model that works with private distributors to ensure that contraceptives are always available in public health facilities. A weak supply chain is a problem that plagues health programs in many African countries, and Senegal was no exception. But since Senegal introduced the Push Model in 2012, contraceptive stock-outs have been reduced from over 80% to less than 2% nationally.

During this trip, I had an opportunity to see the Push Model in action. We met with a team of two private operators who were visiting the Diouroup Health Post in Fatick, several hours from the capital city of Dakar where their company, Cabit SA, is based. Every month, they visit health facilities where they count the products remaining since the last visit, check expiration dates, and enter the data into an electronic system. Then, using real-time data, the team determines how much product is needed for that facility based on consumption patterns and any anticipated demand generation activities that might increase need. They have the supplies on hand in a “mobile warehouse” and can restock the shelves on the spot. Incentives for the private operators help maintain an efficient and effective system, and it frees up clinic staff to do what they do best – provide health services.

The original push model, managed by IntraHealth with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and MSD for Mothers, has been scaled nationally and uses private operators to deliver supplies all the way from the central level to facilities throughout the country. In this pilot site in Fatick, the government’s National Supply Pharmacy delivers the supplies to the district level, but relies on the private sector to go the most difficult “last mile” to reach the health facilities. The original model focused only on contraceptive supplies, but the government is now testing the feasibility of integrating a range of essential health products and intends to fully take over management from IntraHealth.

Many of the stakeholders we met during the trip cited the Push Model as a real success and believe that it can serve as an example for other countries, as well an illustration of how the private sector can make a contribution to public health. Historically, the public health community has paid little attention to the role of the private sector. But stakeholders in Senegal and globally are beginning to recognize that it may be difficult for governments to reach key public health goals alone, and that the private sector has an important role to play.

Other examples of private sector efforts in Senegal include Marie Stopes International’s social franchise network of private clinics in peri-urban areas of Dakar offering quality family planning services. The government is also piloting mutuelles, community health insurance schemes that provide coverage for both public and private care. A local NGO called Ademas is socially marketing family planning products through private pharmacies and working with large companies to distribute bed nets to prevent malaria. And a new foundation called Afrivac has been set up as a public private partnership to engage the private sector in helping to sustain financing for vaccinations.

What I found particularly exciting about the potential

of the private sector in Senegal is the openness of

Minister Coll-Seck and her team, as well as other

stakeholders, to engaging the private sector as an

integral component of the health system. They spoke at

length about the importance of the private sector and

the role it can play – in provision of care,

distribution of commodities, innovation, training of

public sector employees, bringing their skills and

serving their employees. Senegal is indeed ready to

walk with two legs.