With 60 homicides per 100,000 people, Honduras has one of the highest documented murder rates in the world. Exceptional incidence of violent crimes in the Northern Triangle – which includes Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador – is fueled by the drug trade and gang warfare, with recent upticks due to Columbian and Mexican counter-trafficking efforts that have altered smuggling routes in the region. Honduras is beset by acute economic inequality, lack of institutional capacity to enforce laws, and chronic political instability (e.g. the 2009 political coup that forced then-President Manuel Zelaya into exile). Security and counternarcotics have become important national and regional priorities, as well as a centerpiece of bilateral cooperation with the United States.

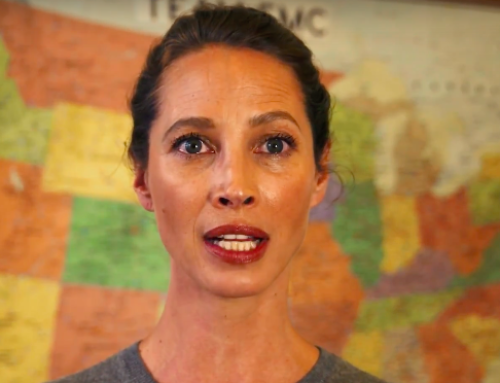

A nurse collects vaccination cards from a group of mothers at Colonia San Miguel health center in Tegucigalpa. Colonia San Miguel has become a focal point for U.S. efforts to work with national authorities to combat and mitigate the effects of gang violence.

Photo Credit: Daniel Mendoza

Despite its violent reputation, Honduras is home to an exceptional public immunization program. I visited Tegucigalpa in mid-January as part of a small CSIS delegation to examine the effect of support from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance in improving access to new and under-utilized vaccines, and the implications of transitioning away from Gavi assistance. Honduras presents an interesting case, as it has been lauded as “a vaccination success story” and is internationally recognized for its high rates of coverage. Yet as a lower-middle-income country, it will be completing its transition away from Gavi support at a time when the United States has reduced its investments in health and is intensifying support for local law enforcement and security forces. Within this context of shifting patterns of bilateral donor engagement, it is all the more important to consider the real and potential impacts of crime and drug-related violence on health in Honduras.

The social effects of the deteriorating security situation have been well documented, including the negative impacts on quality of life, access to services, and overall functioning of the health sector and other services. The associated health costs are equivalent to more than four percent of national GDP, and high rates of sexual assault, mental health disorders, internal displacement, and migration are all seen as direct outcomes. Despite a steady increase in homicides that peaked between 2009 and 2011, Honduras has seen some improvements in health in recent years, particularly around maternal and child survival. Over the last decade, its immunization coverage has remained relatively consistent, and the country was one of the first to introduce two new vaccines, rotavirus (in 2009) and pneumococcal (in 2011), with Gavi support.

To gain a better understanding of how routine immunizations are provided in Honduras, we visited a health center in Colonia San Miguel, a neighborhood in the northern part of Tegucigalpa. Inside, we observed a number of features indicative of the country’s model program: a large group of mothers and young children, waiting for their scheduled appointments; meticulously kept records showing that more than 75 children had been immunized on a recent Monday; a conversation between the head nurse and a woman about her niece’s vaccination needs before providing vitamin A drops, the oral polio vaccine, and a booster of DPT which protects from diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus.

But there were also signs of stress: the compound was plastered with violence prevention posters. The building itself was lined with barbed wire, and there were iron bars covering the interior and exterior windows. The drug trade in Colonia San Miguel is largely controlled by MS13, suggestive of their growing presence in more urban areas of Honduras. This neighborhood has become a focal point for U.S. efforts to work with national authorities to combat and mitigate the effects of gang violence, part of the Model Precinct Program that aims to overhaul the local police force. Through this cross-cutting initiative the U.S. Embassy and Honduran Police have donated medical equipment to the health center we visited, in order to build trust in the community policing model.

What we saw in Colonia San Miguel echoed what surfaced in nearly all of our conversations: that violence is a looming challenge, and that there is concern about its impacts on the immunization program. We repeatedly heard that while facility-based services are generally strong, the presence of maras or youth gangs has created gaps in vaccine delivery. Many families, particularly among poor and socially marginalized groups, are often unable or unwilling to come to health centers due to economic barriers and safety concerns. It is all the more important, therefore, that health care workers are able to go door to door to provide vaccines and conduct surveillance activities. But we heard that some territories have been deemed too unsafe to enter (as there have been reports of attacks and threats against health care workers), and in others, health personnel have been extorted, or forced to pay a “war tax.” While coverage rates are high at the country level, there were concerns about pockets of unvaccinated children, and the importance of local surveillance activities to national and regional certification efforts.

The U.S. government has markedly reduced its bilateral health investments in Honduras in recent years, now focusing primarily on the regional HIV/AIDS program. And in 2016, the country will reach the end of direct support for vaccine purchase, though it will remain eligible to purchase vaccines at the lower Gavi prices for five years beyond the transition. With a GDP per capita of $2,270, there is a sense that Honduras can weather significant reductions in investments from two donors that have played a key role in supporting its immunization program and broader health system. But in addition to the worrisome security situation, the country continues to struggle with a shortage of human resources, limited capacity for surveillance, and outdated cold chain equipment, deficits that could jeopardize its historic success. As the United States shifts away from direct health investments in Honduras and emphasizes assistance aimed at addressing security concerns, it should continue to be mindful of the ways in which health, violence, and governance are inter-related. To support Honduras in sustaining its health gains in a context of political and security challenges, the U.S. should identify opportunities within existing security initiatives and other programs to prioritize health and strengthen advocacy and citizen engagement.

You can read more in our upcoming report examining the Gavi transition in Honduras and Nicaragua.