Senegal has made a conscientious effort to increase access to family planning in an attempt to change the country’s destiny by speeding development, and improving women’s and children’s health. The contraceptive prevalence has increased from 12 to 20 percent in the last five years, but francophone West Africa still lags behind the rest of the continent in increasing access to family planning. Like many countries in sub Saharan Africa, Senegal has a high population growth rate and a large youth bulge. Roughly 60 percent of Senegal’s population is under the age of 20, many without access to education or employment.

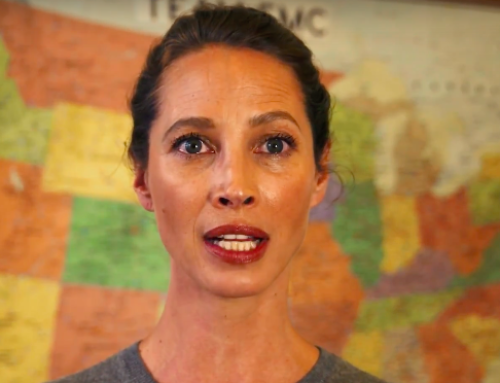

Imam Kane, Kaolack, January 17, 2016

Photo credit: Caitlin Healy

In February, I traveled to Senegal as part of a delegation from the CSIS Task Force on Women’s and Family Health, on behalf of U.S. Representative Richard Hanna, who is a Task Force member. The delegation examined what steps have been taken in Senegal to improve maternal and child health, including nutrition and immunizations, family planning and reproductive health. We visited sites in the capital city of Dakar, as well as rural and remote sites in Kaolack and Kaffrine, and had meetings with religious leaders, health professionals, government officials, non-governmental organizations, and Senegalese women.

With 95 percent of Senegal’s population identifying as Muslim, religion played a significant role in many of these conversations. The opinions of religious leaders are a profoundly revered source of information in Senegal. And while many imams actively promote large families, there are a growing number of religious leaders eager to point out that the Qur’an actually supports birth spacing and breastfeeding newborns for a minimum of two years as a form of family planning.

Imam Mouhamadou Kane is one such example. As the head imam in the city of Kaolack, Imam Kane’s interpretation of Islamic law carries considerable weight. He has a strong following, too: often more than 100 people gather in his mosque during times of prayer.

When asked about his views on family planning, Imam Kane noted, “Islam has actually covered the subject of family planning.” Speaking in French, he continued, “and Islam is not against it. It encourages family planning, so I started encouraging it and talked about it during Friday sermons.”

Because of religious leaders like Imam Kane, public opinion toward family planning is beginning to change in Senegal. Some religious leaders are emphasizing that responsibly utilizing new methods of contraception is about embracing modernity and does not undercut a fidelity to religious law. Imam Kane pointed to his cell phone and said with a smile, “If we reject modern methods [of contraception] then we must also get rid of tablets, phones and eyeglasses.”

We heard similar sentiments from another imam, this time of a different generation. Imam Abdoulaye Lo was a younger religious leader whom we encountered during our visit to the health hut in Horé. Seated in a plastic chair, Imam Lo addressed roughly a hundred men, women and children who were gathered at the health hut for a demonstration of “strategie integrée avancée.” This innovative mobile outreach program provides remote communities with a range of health services, including information and services related to family planning.

Following Imam Lo’s discussion about the benefits family planning, the head nurse in charge of the outreach session, Mrs. Aminata Diouf, spoke passionately about how family planning not only benefits the community, but also the entire nation. If a mother avoids close pregnancies, a child is less likely to be born with health problems, she emphasized to the group. Her message was clear: healthier children will grow with intelligence and be able to help the family and care for their parents.

Mrs. Diouf concluded by linking women’s and children’s health to Senegal’s broader development: “A country’s development is not just something for the government to take on, but it is the responsibility of every Senegalese person.”

There is still significant work to be done in Senegal. However, by working with religious leaders, the Senegalese Ministry of Health and Social Action and health care workers are proving that social progress does not require a departure from the sacred. Rather, through its embrace, families can find ways to improve health outcomes for themselves and their communities.